Cutting timber and stone, especially engineered stone, comes with significantly elevated risks of serious disease, but industries including ours have been slow to act. By Donyale Harrison

Dust seems so innocuous. Half the time it’s too small to even see – and there’s the danger. In many workplaces, minuscule particles travel into our airways, perhaps our noses and throats, perhaps deep into our lungs, where they lodge. If we’re lucky, they’ll sit there quietly. A bit less luck and we might develop asthma or an autoimmune disease. A lot less luck and it could be life-limiting, like cancer or silicosis.

We’re good at worrying about these consequences when we see the tell-tale signs of asbestos: sites are shut down and specialists are called in. But we’re a lot less good about managing our exposure to wood dust and to stone dust, and the wave of disease caused by our casual attitudes to these workplace dangers is starting to break.

Dean Wilson, TABMA’s workplace health and safety officer, is making dust a focus for the association. “The International Agency for Research on Cancer has come out and said that there is documented evidence that both softwood and hardwood dust can cause nasal and throat cancer,” he says.

“I’ve been talking with a hygienist at Workplace Health and Safety Queensland about what their concerns will be with the release of this information and about what businesses need to take into consideration when they are getting people working around timber dust. In short, working with timber now has to comply with the silica dust requirements. Anyone who cuts or sands or works with any timber product should be wearing a fit-tested and fit-for-purpose mask. Wherever possible, workplaces need to provide suitable dust extraction and ventilation and the last resort is the PPE.”

Wilson is naturally concerned with timber, but he notes the crossover with silica dust is more than a PPE grouping. Hardware suppliers across Australia are selling and cutting stone and artificial stone benchtops alongside their wood. Builders are often on site at the same time as bathrooms and kitchens are going in and stone is being cut. Timber-sector workers are at direct risk.

“We have members who are exposed to silica dust from fibrous cement sheeting as well as engineered stone,” Wilson notes, flagging that in many cases, as with timber, the product notes from the manufacturer or supplier ask for ventilation and masks.

“We’ve even had improvement notices handed out to a couple of our members about the cutting of Hebel blocks on their site, because they’ve been cutting them dry, which gives off dust. And the workers weren’t wearing fit-tested face masks.”

And that’s an even bigger worry. Because some types of silica dust have been killing young people.

Artificial stone silicosis

“We described the first case in NSW in 2014,” says Associate Professor Deborah Yates, specialist in occupational lung disease at St Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney and co-chair of the Registry and Clinical Trials Subcommittee for the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand.

“That was a patient who had such severe lung disease he had to have a lung transplant. Since then, there have been at least six deaths Australia-wide in young men. The youngest patient I have is someone who is 21.”

She’s describing artificial stone-associated silicosis, a disease caused by inhaling the dust from cutting artificial stone, such as Caesarstone. It’s a relatively new disease, first noted in Spain in 2010, but it’s different to the classical silicosis that has affected stone miners and masons for millennia.

“The main differentiating feature appears to be that it is much more progressive,” Assoc Prof Yates says. “In other words, it gets worse much faster. The other thing that differentiates it is the fact that patients get autoimmune diseases, which are basically diseases where you make antibodies against yourself and you get skin problems, arthritis and possibly even organ damage.

“The difficulty is we don’t really know why it’s progressing so fast. We think it could be because of the doses of silica they’ve been exposed to, which have been incredibly high – sometimes a thousand times the legislated limits for silica exposure. But it could be other things, for example, exposure to metals or glues, all of which are contained in artificial stone.”

Classical silicosis, which generally affected workers in later life, had dramatically dropped over the past century thanks to improvements in WH&S. The numbers had gone down to such an extent that specialist taskforces had been disbanded and public health programs discontinued. Then, 25-odd years ago, artificial stone products – also known as engineered or reconstituted stone – started popping up on the market. Made of processed quartz bound with adhesives and other ingredients such as resins and dyes, they have silica levels of typically 80–95%, against natural granite’s 25–60% and marble’s less than 5%. They now account for about half of the Australian market for stone surfaces in homes and in commercial builds, thanks to their price point and colour range.

While there are huge international companies selling artificial stone, many of the people cutting and installing it are small-scale contractors who lack legal protections and are often undereducated about the risks, in part because they are often from non-English speaking backgrounds.

Kylie Trounson, an associate at Slater and Gordon, has been working with clients pursuing WorkCover claims for silicosis as well as trying to educate workers and contractors about the risks and their rights.

“In the last few years we’ve seen an emergence of what some people might call a new silicosis crisis worldwide because of the makeup of these engineered stones being very different to natural stone, but workers still working with it in similar ways to how they were working with natural stone,” Trounson says.

“They’re often dry cutting, where the dust just goes absolutely everywhere. It’s very fine dust. I understand from talking to people who work with it that dust needs serious protection, including full ventilation, well-fitted and proper masks and wet cutting equipment – which is really what is required to try and stem the flow of this incredibly fine dust with incredibly high silica content. The lack of that protection is what’s led to where we are now, with some stonemasons now contracting this acute, accelerated silicosis.”

She adds, “The chief novelty is the high silica content. The lack of protection is one issue; the lack of product warnings is the other. PPE is regarded as the last resort in industrial hygiene, with dust extraction and wet cutting being a priority.”

Many of Trounson’s clients are also at the peak of their working career. Even for those with milder forms of disease, it is life-changing, as they must be extremely careful to limit future dust exposure.

“The trouble with tradies is that they have to work with dust,” says Yates. “So they either have to completely change to doing something different, and a lot of these people have no training in skills like computers or office-based work, or they have to try and get a job in something related but less dusty, which is difficult, especially because most are in their 40s. And the moment someone finds out they have a dust disease, they often don’t want to employ them.”

Right now, Yates emphasises that we do not know what the safe levels of safe exposure to artificial stone dust are.

“All this has resulted in the legislated limit for exposure being halved,” she says, “but anecdotally, people are still working with a lot of silica. Dry cutting has been banned in most, but not all, of Australia. It shouldn’t have been allowed in the first place. It’s been known about as a cause of silicosis for about 150 years.”

So far the cases have been in workers with high levels of direct exposure, rather than in family members or other workers on site, as was commonly the case with asbestos, but Yates cautions that it’s early days and these remain possibilities in the future. “People may be exposed if they’re working in building new construction, in kitchens and bathrooms particularly,” she says.

Taking action

There’s a mixed bag when it comes to official responses to artificial-stone silicosis and other dust diseases. ‘Workers’ as defined in industrial legislation – all PAYG employees and some contractors – have reasonably effective protections and various regulatory bodies looking out for their interests.

“This is a focus with the various state WorkCover authorities,” Wilson says. “With timber, at mills and fabricators, they’re looking at how clean the areas are around saws, how often the saw itself is cleaned, making sure businesses aren’t using compressed air to blow that dust away because that makes the dust more airborne. The concern is that it’s not the physical dust that you can actually see, it’s the micro, airborne dust that goes into the nasal and throat cavities that can start disease, which is a similar fibrotic disease to silicosis.

“One of our industry members failed an inspection recently. This workplace provided dust masks for people to use, but because they weren’t fit-tested to suit the operator, the inspector found that company in breach. They were issued with an improvement notice and instructed to get all their people fit tested and supplied with appropriate masks – most often N95 masks or a full respirator.”

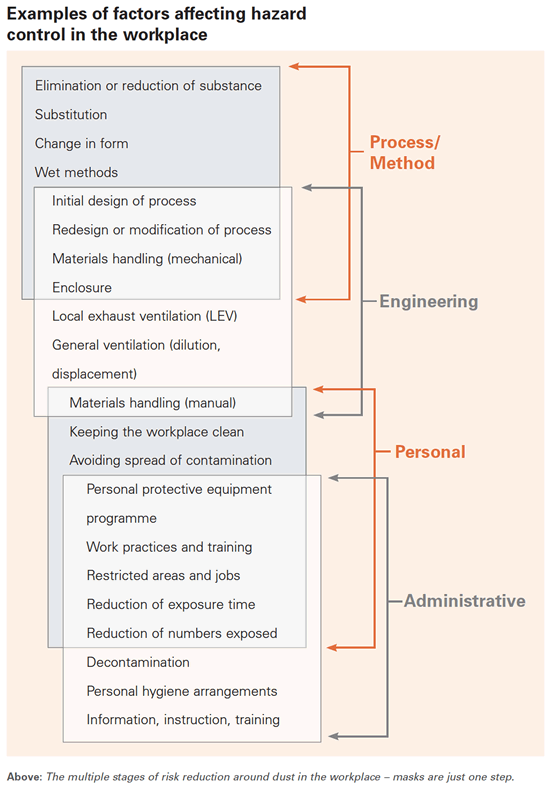

Masks are only one step. They work best in combination with multiple other measures to reduce risk (see Examples of factors affecting hazard control in the workplace graphic, below) and first that risk needs to be measured. In many workplaces, only certain areas near saws or finishing tables have high dust levels, in others, it’s the entire plant. You may need to have fitted masks for every staff member, or just a few with everyone else protected by a dust control/extraction system and ventilation.

Defined ‘workers’ who get sick do have access to the various state-based workers compensation schemes for income support, bill assistance and possible payouts. But not everyone is a worker. Many of those cutting artificial stone are defined as just contractors and they have far fewer protections. Tragically, they often also have far less information about the risks. Many are one- or two-person operations and are clustered in migrant communities.

Victorian-based Slater and Gordon workers’ compensation principal lawyer Neil Andrews has been working with affected people in considering whether to pursue a class action against the manufacturers of artificial stone. “Initially, it was difficult to identify just how many workers had been exposed to silica dust, as a large number of stonemasons are migrants and refugees on contracts who speak limited English or hold positions in workplaces that were often non-unionised,” he says. “This was further complicated by the small workshops scattered throughout Victoria making it hard for the regulators (Victorian Government’s WorkSafe) to keep track of their operations.”

In November 2017, Slater and Gordon set up a national silicosis register.

“It has provided a sense of how many people have been exposed, and enabled us to assist them to access appropriate compensation. It has also increased our knowledge of the exposures that cause the disease,” Andrews says.

Trounson describes how the firm has assisted those who are eligible to access help through established schemes: “[They] can access benefits and will probably be paid adequate compensation through the workers compensation schemes, and we always say to people that’s where they go first if they are a worker, because WorkSafe is well aware of silicosis, they understand the disease and potentially in some cases there will be significant amounts of compensation paid out.

“But the real problem is the gap for these people who are not considered workers. They’re not entitled to anything. There’s no one to pay their medical bills or cover their lost income or in any way pay for the fact they may die early. That’s why we’ve been looking into this issue from a class action perspective against the manufacturers.”

Every expert I spoke with expressed frustration at the fact Australian workplaces aren’t taking dust issues seriously enough. Both lawyers and Wilson noted this could turn out to be an extremely false economy in the long run, pointing to strict compliance codes that have been introduced for businesses working with silica and are being introduced for other dust-producing workplaces.

“If an employer has been negligent and failed to comply with their duty of care to keep their workers safe, there could be legal consequences,” says Andrews. “Sadly, the threat of a worker falling ill and taking legal action against their workplace is not always an effective measure to ensure businesses operate ethically.”

But a word stronger than frustration is required for their attitudes towards the manufacturers. Assoc Prof Yates described herself as “a bit bitter” about them, noting that Caesarstone’s reaction to doctors in Israel warning of this new silicosis threat had been legal threats, forcing the researchers who broke the news to change the name of their article, removing the word ‘Caesarstone’.

Andrews is no less damning: “The engineered stone manufacturers bear significant culpability for the current silicosis cases,” he says.

“Their products can contain up to 90–95% silica, whereas natural stone such as granite may contain from 20–60% silica. Given silicosis is a very long recognised industrial disease and the dangers of inhaling crystalline silica dust have been known for so long, we are concerned that the manufacturers are not contributing to the compensation paid to people who have contracted silica-related diseases through their work, or to a greater awareness about the inherent risks and dangers of working with the products they make.”

Reshaping the future

The one faint upside of artificial-stone silicosis is that it has reminded us that dust diseases are not a thing of the past. Workplaces, some trade unions, regulatory authorities, much of the legal and medical profession, and state and federal governments are all starting to act together on the issue.

Assoc Prof Yates urges anyone who’s been exposed to any kind of silica to make sure they have the dust levels in their workplace measured. “This is something that is actually already legislated,” she says. “If an employer suspects that workers might be exposed to crystalline free silica, they are meant to sample the dust and make sure that the appropriate dust control measures are implemented. But this just doesn’t happen a lot of the time.

“So if the employer isn’t doing it, the employee should perhaps remind them. There is an obligation on behalf of the employer to provide a worker with information about potentially toxic substances to which they may be exposed. They’re meant to provide them with a materials safety data sheet. The problem is, a lot of the artificial stones just don’t have information about what’s in them, so nobody knows exactly what they contain. And when the poor old workers ask for some of the legislated safety conditions to be applied, they worry they’re at risk of getting sacked.”

The fragile employment conditions of many people in the stone cutting sector make it hard for change to come from the bottom up. Timber industry workers are often in a good position to support them by putting pressure on companies doing the wrong thing, thanks to a better protected and more unionised workforce.

While acknowledging masks are only the last step in dust suppression, Yates says, “For a lot of the people I see, their employers have been incredibly reluctant to give them regularly changed, fit-tested masks. There is an expense, but it’s tiny in comparison with the long-term damage that this can do. The only way workers will be able to actually change this is by all getting together and working as a group. So if there’s a carpenter or builder who sees there’s a stonemason who’s being exposed to dust, he should be able to able to tell him and maybe also let SafeWork know, because this is not right!”

Meanwhile, change is coming from the top. Andrews says, “The Victorian and Queensland State Governments have led the way in ensuring all stonemasons have health checks and undergo testing. The Victorian Government has been running an awareness campaign to highlight the risks of working with artificial stone, and has hosted events to educate doctors, GPs and respiratory physicians so they can identify the condition.

“The Victorian WorkCover Authority has tested workers in most stonemasons businesses in Victoria and identified workers suffering from silicosis. That has prompted a large rise in WorkCover claims of this type due to awareness. State-wide bans on uncontrolled dry cutting of materials that contain crystalline silica dust were announced in Queensland first, then Victoria and NSW.”

Outside of NSW, diagnoses of silicosis have led to case finding studies, “Which means that, like Covid, they’ve actually gone out to the workplace and examined all the workers who were exposed,” says Yates.

Assoc Prof Yates is also involved with the National Dust Diseases Taskforce, which is charged with developing a national approach to the prevention, early identification, control and management of occupational dust diseases in Australia. The Taskforce is due to hand down its final report by 30 June.

“The fallout of that is going to be a national reporting service, we hope,” Yates says. “Provided the federal government funds it. It’s a big ask but we’re trying. The problem is that the reporting probably won’t help people other than 20 years on, because there’s this long latency period.”

Yates is one of many lung specialists hoping that a national screening service for workers who are exposed to dust will be another outcome. There can be a 20-year gap between exposure and showing signs of disease, so someone exposed as an apprentice might not get sick until they are in their 40s with a mortgage and a young family.

Regular screening that’s retained on a national database will show damage earlier and make life easier for people pursuing claims, as well as help legislators and regulators see patterns of illness and work to prevent future cases. Yates also hopes for a system similar to the investigative branch of the National Institute for Occupational Safety in the US. In the meantime, she recommends people working with dust have regular checks by independent doctors, “ask for copies of the information and keep it yourself, or give it to your wife to keep as that’s often the safest thing.”

While there are treatments for some dust diseases, these include restricting future dust exposure, which means a significant change in work and sometimes earnings. For progressive silicosis, options are limited, but treatments in trial form, using an antifibrotic tablet called nintedanib, are available. Physically washing out the lungs (whole lung lavage) is invasive, requiring intensive care admission, and has not yet been proved to work. Lung transplants are difficult to obtain and prevention remains the goal.

Trounson and her colleagues are continuing to get the word out directly. “I’m having a chat over Zoom with some leaders from the Afghan Hazara community tonight,” she says, “because they’ve come to us concerned that they have many self-employed people within their community who are cutting stone.

”At the moment it’s really trying to access those people, find out who they are, ask if they’re aware of the risks and can they therefore change their work practices? But also they absolutely need to be tested, because if there’s any sign of disease there, they have to stop work straight away. It’s a big problem if they’re not considered to be a ‘worker’ and cannot access any compensation for lost income.”

Previously Trounson has spoken directly to Vietnamese community groups, taking advantage of their established networks and translators to talk with people who are often hesitant to seek out legal or medical help. “I feel we’re imparting something that will be helpful. And it’s symbiotic; they’re telling us things that we didn’t know about the type of people who are doing this work and that gets us thinking as to how we might be able to help them.”

As far as the timber sector is concerned, with the new evidence showing timber dust as a potential cancer cause, Wilson says the days of being casual about dust diseases are past. “Now the risks are exposed, workplaces need to make sure they’re doing the right thing,” he says.

“There are plenty of people and organisations out there who do good fit testing, I’m doing a course myself to provide it as a service to our members. Too often in our industry, safety is one of those things we’ll think about when we haven’t got any work to do. Everyone seems to be always worried about the sales side of things and not the safety. But if they get safety wrong it can cost them a lot more than what they make in sales.”

Assoc Prof Yates says, “I had a 45-year-old patient who died, and he had small children, two and seven. It really made me very upset. He was a nice Vietnamese man who’d trained as an engineer at Sydney Uni and started cutting artificial stone in the holidays and found he could make a lot of money. It’s quite a skilled job and very satisfying with these lovely smooth surfaces. And so he kept on doing it. He didn’t know anything about the hazards. And he died as a result.

“The trouble with prevention is that it is not “sexy”. But in the long run, it will save lives and also costs. Artificial stone manufacturers are making millions and have known about this for several years. There is no excuse for selling something unlabelled which is likely to kill a worker. Not anymore.”

For more, visit www.slatergordon.com.au/silicaclassaction, www.tabma.com.au, www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/ohp-nat-dust-disease-taskforce.htm and www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/silica for details on managing silica.