In this ongoing series, we look at the move to panelisation and offsite construction in Australia. This month, we talk with three leading businesses providing panelised solutions.

While this story was being written, most Australians went back into lockdown. This is definitely a time of very real anxiety and uncertainty, but it’s also a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to reassess what we want our ‘normal’ to be in the future.

The timber and construction industries have been cycling through many of the same repeating problems in recent decades. Right now, many of these are coinciding and are severe for various reasons, but none are going to disappear when the pandemic eventually ends. There will still not be enough Australian plantations to provide the fibre resource we currently demand. There won’t be enough skilled labourers to meet the needs of builders and housing will remain unaffordable for a large number of people.

We can keep doing the same things and making optimistic announcements that the outcome will change, or we can adopt a more rational approach and move to newer methods of construction that better manage and respond to sundry shortfalls.

Panelisation is only ‘newer’ in the broadest sense. Across Europe, it was a key part of rebuilding post WWII. While that architecture was often plainer and more repetitive than the current incarnations, the core advantages of the system were in place even then. Buildings could be constructed in sections, inside. The panels and the workers stayed clean and dry, work was done at ground level rather than at height and tricky jobs like insulating walls became easy in the controlled environment of a prefabrication plant, leading to a higher quality of finish.

At the end of the process, the wall panels and floor and ceiling cassettes were stacked onto trucks, driven to site and slotted into place with a crane and a handful of carpenters, ready for secondary trades to come in and complete the build.

Things are more technologically advanced now, from the highly detailed preliminary work that goes into modern Design for Manufacture and Assembly (DfMA) to the potential to use EWP and other specialist materials. But the fundamental benefits that saw the process adopted in Europe remain in place in Australia, even though it’s a much less mature building method here.

As a method, it requires careful planning, which both lowers the amount of material required and ensures its most economical use. It requires fewer carpenters working on site, and less physical effort from those who are there. Much of the manufacture can be automated, but basic wall panels require only a butterfly table and a decent set of fabricators, all of which help address skill and material shortages.

Instead of producing each build as one-off construction, most panelised construction relies on a kit of parts – elements that can be fabricated efficiently in volume then combined in ways that suit each specific build. These are also generally more re-usable at the building’s end of life and can be designed for easy disassembly.

The design is key. Every successful panelised build requires the early and enthusiastic engagement of the designer and manufacturer by the builder and developers (or government agency) to produce a structure that represents the optimal solution for the site, for manufacture and assembly and for the end users.

It’s in this collaborative process that offsite panelisation soars as a construction method, slashing time spent building on site as well as delivering strong efficiencies in materials and high-quality results.

In coming months we’ll be talking to machinery suppliers and specialist construction companies and about the money side of panelisation. This month, we talk to three leaders in the field about their current projects and current issues.

Housing New Zealand

Ironically, one of the panelisation firms doing great work in Australia is currently sending much of it across the ditch to New Zealand.

“We’ve delivered four projects now into Kainga Ora (New Zealand’s national social housing program), through our client, an Australian company called IMB,” says Tim Newman, general manager at Timber Building Systems (TBS).

“The first three projects were three-storey walk-ups, with a separate apartment on each level accessed through a common staircase. The one we’re finishing now is a five-storey multi-res that’s all in one complex with a common stairwell. It’s getting topped out through the end of August.”

Several factors combined to make it more efficient to ship the product out of Australia. “The key one is they’ve got a lot of social housing to provide,” Newman says. “The amount of buildings they need to provide to help with their social housing issue is a whole lot more than their local industry can deliver in the time frame they need to achieve it. They’re also very bullish on using different prefabricated models to evaluate the results of each type: they’ve done volumetric, they’ve done panelised, they’ve done CLT.”

It’s worth taking a moment for some definitions. Offsite is pretty straightforward: the build is mostly constructed in a facility away from the building site. Modularisation is about breaking a build down into component parts and constructing those parts before assembling them. It can be volumetric or panelised. Volumetric is the sort of modular construction many of us know from cabins or portable classrooms. Modules are delivered to site and essentially lowered onto a footing then connected to services. Panelised delivers flat wall panels, often along with floor and roof cassettes, then stands them up into a building. Panels may be clad on site or may arrive with all finishes and fittings already in place. CLT panels are made out of mass timber rather than based on light timber wall frames and can be clad, or have various elements routed into the timber.

“Most of what we do is panelised, though, if needed, we will do a volumetric style small module, like staircases and so forth,” Newman says.

“Panels are much easier to move than a volumetric module. We can stack eight panels on one of our flat racks and each panel can be up to 10m long by 4m high. That’s quite a significant amount of building we can put on one six-foot base. We don’t ship much air, especially compared to volumetric.”

Surprisingly, Newman’s background is automotive “I came out of Holden,” he says. “There’s over 300 years of cumulative manufacturing experience in TBS and it’s all ex-automotive, ranging from our production manager Darren Wylie who has spent most of his career working within Toyota lean production systems, to my project management and engineering background and then some of our design team who were in the CAD office. Even our purchasing person is from an automotive industry supplier.

“What that allows us to do is to take a building, break it into parts and then design a manufacturing system to suit the building. Which means that we can build at rate. Because the only way to succeed in this business is to build at a good rate.”

DfMA has been a part of the Australian automotive industry for decades and generations of young engineers going into the industry were taught its principles, so the TBS team are well placed to help explain the possibilities and benefits of using panelised systems to would-be clients.

“Plus there’s a whole suite of other tools we’ve brought across from automotive that the construction side of the industry hasn’t yet picked up,” says Newman.

“We talk about months in design, weeks in manufacturing, days on site. We spend a lot of time in the upfront design, making sure everything’s spot on; our shop drawings are very complicated. Then once we hit the go button on manufacture, it happens pretty quickly and it’s an even shorter time frame to install it.”

Not everyone has internalised what that means. “I have people ring and say, ‘I want a three-storey building.’ And we say, ‘It’s four weeks to manufacture it.’ And they’ll say, ‘Great, so in four weeks’ time, can you deliver it?’,” Newman says.

“No. It’s going to take months to design. But that’s where the savings are, because you haven’t cut any material. You haven’t used any labour on site. You’re working out everything beforehand. No-one’s hanging three storeys up trying to nail a truss in and work it out at the same time. It’s all worked out standing down the shop floor.”

Newman has found that developers still tend to focus on upfront costs, rather than appreciating the accumulation of savings through the offsite process. “You’ve often got to do a full offsite build to appreciate the cost savings on site and the cost savings to the project. We typically build without any scaffolding on site at all. You reduce the time you need site sheds and project managers on site. Rectifications are very rare because everything’s been signed off in CAD, and we find efficiencies through repeatability. All those hidden costs that come up through the build are removed.”

Repetition or remote

At the moment, the majority of offsite panelisation work in Australia is for government builds, education and multi-residential. “There are some obvious reasons for that,” says Tim Strong, general manager Viridi Group.

“Look at your standard domestic low-rise market, what I call the spec home. It’s cutthroat. They work on very tight margins and pit frame and truss companies against each other to keep those prices down.

“Until the timber shortage struck, the frame and truss companies were working on fairly low margins but still able to complete jobs very quickly. And once on site, your carpenters could whack things in quickly. So it was hard for the prefabricated product to compete there; we need to be looking at different elements to find savings or justify the superior quality of the product.”

That’s led to three main markets for panelised construction. The first is medium density/multi-res. “That’s a completely different standard, where we’ve always been able to come in and compete,” Strong says. “If we’ve got 64 houses for example, that sort of job is geared up more commercially. It already comes with a preliminary process and then we come into our own, because our prelims are all about finding the most efficiencies in the build, and then the affordability gain on speed of construction pays for itself and more than covers the extra costs around transport and cranage.”

The second market is regional, where panelisation competes thanks to the higher domestic construction costs outside major cities. “We’re finding that rural work, whether it’s a one-off house, or multiples, is an area where we are competitive on price,” says Strong. “The local demand on tradies in these areas is quite high, which pushes prices up. We can deliver product cost-effectively to many regional areas and work with local installers of local builders. I’ve got jobs coming up in the Hunter Valley, in Newcastle and down near Jindabyne.”

The savings are even more notable when working on difficult sites, such as those with a significant slope or some distance from town, where even a short domestic build will blow out when it has to factor in four hours of travel time per day over months versus a few days at most erecting a panelised structure.

The final market is specialty builds. “I’m working with a client now around using fire-retardant timber. It’s a new product that’s coming out from ITI and we’re looking at using that in products for BAL 40 and BAL 29 areas. For other clients, we’ve built to Passive House standards,” Strong says.

“This is where the higher standard of quality achievable offsite is the key difference. One of the jobs we’re working on at the moment is with a Newcastle architect. She’s got really nice designs where she wants to have airtightness layers and better installation. She wants physical thermal barriers on the outside of walls, not just the sarking – it’s a better product than the spec home.

“Adding layers to walls in our factory is cost effective. If we’re producing a wall for a house and you want to add a different layer, the labour cost doesn’t increase much, it’s just the material costs. Doing that on a traditional build on site is much more difficult: it costs more and there’s more likelihood of problems with the final product.”

As a relatively new company, Viridi is looking to grow its share of all three parts of the main panelised market.

“Where we’re at right now with our current facility, I’m not trying to compete against spec homes,” Strong says. “But that’s likely to change with my projected stage two upgrade where I’ve got more automation and significantly higher productivity. That will be a game-changer in cost of product and make Viridi competitive in all markets.”

The stage two facility will be fitted out with machinery from Randek, Viridi’s current wall line supplier. “We’ve been working with them on our designs and we’re just doing proof of concept now,” says Strong. “Then, once we get the pipeline of work coming through, then we’ll press the button on our upgrade, which will take around about 18 months to be manufactured, delivered and installed.”

Managing supply

Drouin West Timber and Truss (DWTT) has been a pioneer in innovation for most of its 60-year history and was one of the earliest leaders in Australian panelisation. Peter Ward, managing director at DWTT, has recently seen the company through the design, development and opening of its new FutureFit offsite manufacting facility, which came on line just as Covid hit last year.

While the new facility delivers highly efficient automated production, Ward had planned for more. “We’re certainly seeing a lot of interest in the offsite area,” he says, “but we’ve got a couple of large projects on at the moment that we’re heavily committed to until the end of the year and beyond, so we’re not being able to take advantage of that interest, because we’re running close to capacity, given Australia-wide supply issues with timber, LVL beams and so on.

“We’re running one shift at maximum capacity at the moment. Right now, there would be opportunities to be running a second shift, but we can’t get materials to do it.”

DWTT is one of the most successful Australian manufacturers working in panelisation, but even Ward and his team have felt the pressure of Australian construction’s obsession with low price tags. “We did a number of projects with one of the very large builders, and it was a good relationship while it lasted,” Ward says. “But they seemed to be under continual pressure on costs. In turn, we were continually put under pressure with them trying to drive the price down to something closer to traditional F&T, ignoring all the benefits of our system.

“In the end, we had to make the call that there was other work where we weren’t getting anything near those pressure points, so we parted ways, amicably.”

Happily, other developers and builders have been more comfortable with changing where the expenses are in a build in return for the multiple benefits they can achieve. DWTT’s new facility demonstrates the strength of demand in the sector.

Ward says, “The machinery for the new plant is a combination of Weinmann, made in Germany, which is our big wall panel line. They’re supplied through Homag Australia and then we’ve got Hundegger linear saws from Germany as well and our timber picking and retrieval systems are from America. Add to that our conventional wall framing lines from Multinail in Queensland and some of the more minor equipment, supplied by local suppliers. Finally there’s our C4 truss line automation system that was supplied out of America from ITW.”

(See future parts of this series for more detail on the DWTT plant and processes.)

But, like everyone else, Ward has hit the wall that is current supply shortages.

“We didn’t build the new factory and make all our investments to have it run on a single shift basis, but since Covid, with supply issues, we can’t get enough volume of materials to warrant a second shift,” he says. “We’d need several hundred cubic metres more timber and beams, etc, and we just can’t get that.

“We’re struggling to get to the volumes that let us run full bore on the one shift. We’re doing it, but if we ramp up beyond that or run any overtime or whatever else to try and quicken up supply to our clients, we pinch ourselves with material supplies.”

Every manufacturer we spoke with agreed that government had a positive role to play in expanding panelisation, but Ward hopes there will be a degree of caution with future stimulus. “Ideally, things like the flagged big Victorian investment in social housing would be held for when the current bubble bursts,” he says, pointing to the 40% YOY jump in housing starts to March 2021.

“This level of housing growth is unsustainable, particularly when we have no immigration at the moment. I know we’re having a minor baby boom, but they won’t be buying houses for at least 25 years.”

Ward acknowledges the housing boom is being driven by low interest rates, rather than immigration, but worries the current situation is driving unaffordability. One of his daughters and her partner have recently moved to a small property in Sydney’s Inner West, and he was horrified to hear of their rental costs. “Paying $800 a week for a little cottage. How do you save?” Ward asks. “They’re both professionals, but it’s very difficult to save any substantial amount with the living costs like that and you can’t get ahead of the game because the prices are going up too fast.”

Accordingly, Ward would like to see governments take the lead. “Once this backlog is built, which might be a year or more, I think that would be the time for further stimulus packages like social and government housing,” Ward says. “And they’ll be warranted to get people into permanent housing who would otherwise never get into it.”

Driving demand

Newman has seen an upturn in enquiries, but isn’t sure if they’re from people who want panelisation’s efficiencies or who just can’t get any timber.

“Some of them see us as a way of providing timber that isn’t available in the market, but I have the same constraints as the rest of the market,” Newman says. “If I haven’t got a project purchased months out and the timber organised, I’m not going to be able to take that project.

“I think some of the current enquiries are just desperate for ways to get their projects completed. I don’t think the market fully understands what we do yet.”

He agrees with Ward that there’s a strong role for governments to play, particularly when it comes to their own procurement for infrastructure projects. “If we’re doing a project that’s government-backed that’s certainly valuable to us and delivers security,” Newman says. “Because the type of prefabrication we do is a huge investment in plant and equipment. We’re working with significant pieces of machinery from Hundegger, backed up by custom pieces.

“And that creates a Catch-22. Do you invest early so you have the capabilities to do the big projects, but if they don’t come off, you’ve got a massive overhead that you’ve got to keep alive? Or do you grow slowly? We think that so far, we’ve found the middle ground, just growing enough to do what’s on the books.”

Strong also sees the benefits in working with governments. More than half of his current projects are in the education sector, a mix of public and private schools.

“Back in 2008, the Building the Education Revolution program had to do a lot of work in schools quickly. So offsite manufacturing, especially volumetric module work became quite a big thing,” Strong says.

“The costing of volumetric has really allowed us to come in because with our panelisation solution and our kit of parts we’re able to be more competitive than volumetric, but deliver in a similar time frame to them. And both methods have shorter time frames on school sites than a conventional build.”

In the optimal case, Viridi is delivering schools with pricing that competes with conventional builds, as well as timing that equals the speed of volumetric.

“These are greenfield sites,” says Strong, “brand new schools. We can deliver quickly and we can also be cost effective because our structures are lighter and bring more benefits around engineering and using different materials to get pricing down.

“On schools, prelims are always high. For a tier-two builder coming in doing education, if we can shave 30% off the program, then that’s a lot of money when it comes to prelims.”

School Infrastructure NSW has what amounts to an internal DfMA team, who champion the notion of the kit of parts and work closely with manufacturers.

“We’ve been working with that team’s lead on the school at Fern Bay that we’re currently delivering,” Strong says.

“The team have been a force for the project, which is the new prototype of the kit of parts flat-pack school. It’s a four-classroom module with lightweight timber wall panels and floor cassettes, plus trussed roof modules that are prefabbed with all the installation. We’re working with a company out of Melbourne for the pre-wiring, so all the electrical work will be in our flat pack modules and it’s all click and play. Within a day or so, the sparky has that building live with power.”

When I spoke with Strong two months ago for another story, he had just signed off that contract.

“We started manufacture on Monday,” he says, “and I’ll finish manufacturing next week and we’ll start delivering it in 10 or so days and then we’ll install it over four days.”

TBS is another member of the panel for supplying panelised components to Schools Infrastructure NSW. “Victoria and South Australia are developing their educational infrastructure and New South Wales has done a very targeted approach on DfMA buildings,” Newman says.

“It would be ideal if they were contracting more than one building at a time,” he adds.

“If they were contracting multiple builds, as New Zealand does, that would be the step that would give us the confidence to take the next steps immediately in our expansion. They’re working towards it, but that’s still a fair way off. There’s not that many panelised suppliers, not as many as there should be. If this procurement was done differently, that could enable a number of us to grow.”

Additionally, some of these purchasing structures are more complicated than a direct government purchase. “ We need to keep working towards a more targeted purchasing structure where the prefabricated suppler is not so detached from the end client The best models of DfMA deliberately engage prefabricated suppliers early on, instead of allowing the supply chain to do it.”

Panelised wishlists

All three experts agreed the sector is primed for growth but will need more people working in it.

“At Viridi, we’re keen to work with more fabricators who don’t have the facilities but still want to be supplying, say, floor and roof cassettes to their builders,” Strong says. “We could assist them in manufacturing those components and work with those fabricators until they reach the point where they get comfortable and they see the market. Then they can go out there and invest in a floor cassette machine themselves.

“If I could do that with three or four fabricators out there and support them to become fabricators of prefabbed modules or components themselves, then I’d be a happy man. We need more people to create a bigger market of change. Until that happens and everyone gets more confidence around it, people aren’t going to be willing to invest in the machinery – which costs around $600,000 to $9 million – to become the type of fabricator that we are.”

Strong points to some cutthroat behaviour in the industry that has served to push down prices in F&T and, in the past, of timber products. “We end up with this market of non-sustainable businesses that can’t make a profit to stay open,” he says.

Part of his work on the Fern Bay school involves information gathering – both on the build and the school – to report on savings and building performance. Past builds pre-Viridi have delivered figures of 12-15% in time savings and 8-10% in cost savings.

“We’re not all competitors,” Strong says. ‘For those of us working in panelisation, if we looked at each other as a team of people who are going to supply an industry and educate, I think that would change the way that people look at offsite manufacturing, flat pack modules and prefabrication.”

It’s a sentiment that has general agreement. “We’ve seen a lot of people go to Europe and look at panelisation there, but they come back and keep working as they always have,” says Newman.

“Some of that is being conservative; they’ve been making good money doing what they’ve always done for a long time. So why change? But I think there’s also nervousness about the risks of the new.

“We’ve got to just keep putting out buildings and showing they’re actually better than the ones built conventionally. From a competition point of view, our prefab builds need to be competing against conventional, not against each other; that’s the bottom line,” Newman concludes.

At the moment, there’s enough on to keep all three companies busy into 2022 at least. “I’ve got a project for a company called Ultrabuild at Double Bay, which is a two-storey extension on top of a commercial building,” says Strong. “That’s two levels of floor cassettes and then a level of roof cassettes that we’re providing on that solution. It’s a tight site and materials handling is hard so an offsite manufactured solution is really the only way of building that.

“Then we’ve got 12 cabins made up of two modules each using our floor cassette line and our wall panel line. We’re actually assembling them to make five-star, fully pre-fabbed volumetric cabins in the factory and they’re going up to Hayman Island. We start on them in four weeks’ time.”

TBS is similarly busy, but Newman has some dreams. “If we could have a few items ticked off our wishlist for both us and panelisation growing in general, they might include early engagement by government bodies,” he says.

“That’s being brought on very early to help drive the building design to get something that looks great and can be panelised and manufactured at a good rate. Because then we can maximise efficiencies and deliver a significant amount of social housing in a short period of time. But we need to be on early.

“The second one is long-term contracts from those agencies, because in manufacturing you need a long-term contract to be able to justify the R&D and equipment to grow the business. In the automotive days, when you got the business to supply a part for the manufacture of a car, that was a three- or four-year contract and you had the business set for that time. Which is typical in manufacturing. But in construction, often you’re securing a two-month job, then it’s gone and then you’re searching for the next one. That makes manufacturing difficult because you don’t have a long-term supply. So we’re looking for long-term partners.

“If I got those two things, I’d be extremely happy.”

For more, visit http://dwtt.com.au, www.tbsaus.com.au and https://viridigroup.com.au

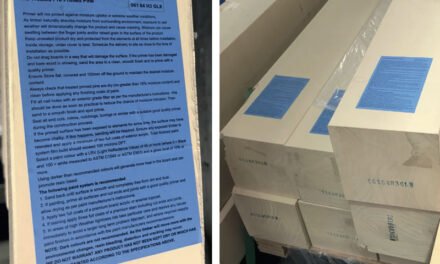

Image: Completed panels are packed for protection and trucked to site (see bundles left of image) then craned into position for a quick installation, ready for floor or roof cassettes above. Courtesy TBS.