One of the UK’s leading engineers and building safety experts recently talked with young Australian designers. This is a condensed version of her opinion piece.

Dame Judith Hackitt recently visited Australia as a guest of RMIT’s School of Property, Construction and Project Management. Currently the Chair of the Independent Review of Building Regulations and Fire Safety, this decorated British engineer presented to industry, government and community representatives on her Building a Safer Future final report.

The extent to which builders have used inflammable cladding on buildings in Australia and the UK has shocked us all since its discovery in the wake of serious fires, including the tragedy at Grenfell Tower.

The people with the highest level of concern are those who are living in these buildings. But who should pay for the remediation work? It feels wrong for those who live there to be asked to fund a problem caused by someone else. But if Government pays doesn’t that mean those who cut the corners in the first place get let off the hook rather than held to account? Of course it does. But waiting for those responsible to do the right thing won’t work either – some might, but many will instigate lengthy legal proceedings to argue the case. That leaves residents living in buildings they are deeply concerned about. It’s a real Catch 22 – or is it?

The UK Government and the Government of Victoria have taken the decision to fund removal of cladding and remediation out of the public purse. But the battle to hold those responsible to account must go on – through the courts if necessary – to recoup as much as possible of that money.

It can’t stop there either. In the last few years we have learned a great deal about the state of our buildings – particularly high-rise residential properties and it isn’t pretty.

The competency of large parts of the workforce is lacking, which means they don’t understand the importance of critical safety features they may be installing in a building and how they need to be installed to be effective;

Even when enforcement action is taken against those who break the rules, the sanctions are so weak as to make it unlikely that lessons will be learned, and practices changed;

Record keeping is poor which means that after a building is complete no one really knows whether it was built to design and if it is fit for purpose.

This is about much more than cladding! We need to drive a massive culture change in the construction and built environment sectors that holds people accountable for designing, building, maintaining and managing buildings that are safe for people to live in throughout the full life cycle. Residents must come first, they must have a voice to raise their concerns and the whole industry needs to be held to account for its responsibilities for their safety.

That will require substantive regulatory change and for leaders within the construction industry to stand up and be counted. Those who do build with users in mind, those who understand that quality matters and have already implemented good practices should become preferred suppliers.

Removing dangerous cladding is a very important first step on a long journey; let us not fall into the trap of thinking we’ve fixed the problem when we’ve fixed the cladding.

To read the full Building a Safer Future Report, click this link.

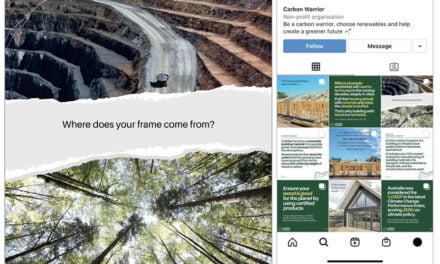

Image: Dame Judith Hackitt told RMIT students that removing dangerous and banned materials from façades was essential, but only a starting point for renewing confidence in high-rise residential buildings.