Creating quality products from lower-rated timbers and supplying busy customers with affordable components is a winning strategy for Programmed Timber Supplies.

Waste is the bane of the timber industry. Whether it’s idle time on the plant floor, missing out on a contract because you can’t meet the sudden demand or turning functional timber into low-end products because you can’t use it for a higher-value product, most companies see some value frittered away.

Not so at Programmed Timber Supplies. Sprawling across most of a block in the Western Sydney suburb of St Marys, the business is the brainchild of Warwick and Helen Drysdale, who 20 years ago decided there was a gap in the market for a company that could bring more economies to others across the industry.

The plan was threefold: take on the repeat jobs that aren’t economical for producers to do themselves, set up regular deliveries for major customers to reduce admin work, and make good use of the timber that was ‘leftover’, turning it into high-end product.

“I was working at a major producer,” says Warwick, “and I saw how they were focused on producing all these big long lengths of wood. I realised there was an opportunity to take the short bits they didn’t use and create a product that utilised the wood fibre better.”

That was the seed of Programmed Timber Supplies. Timber that producers don’t sell as high-graded long-length material is carefully sorted and cut into suitable, mostly high-value, end products.

“There’s still an awful lot of good wood in all that stuff,” Warwick explains. “But most big saw mills have to act like sausage factories and turn out the same things over and over. We realised that we could be chasing 18 or 20 good, different products out of the one piece of wood.”

From dirt floor to high tech

Of course, things didn’t start out with that level of complexity. In the early days, the company cut components for whoever needed them, from fabricators to furniture makers. They were in a rented factory in Seven Hills with one saw and one forklift.

“If Helen was cutting the wood, I was driving the forklift, and if she was driving the lift, I was cutting the wood,” Warwick says.

They quickly outgrew their site and moved to St Marys in late 2001, buying a former ADI site that included its own bomb shelter and had been used by an engineering firm.

“We needed more heavy machinery,” says Helen (who stepped back her involvement a few years ago for more family time). “And so we needed the security of owning the site. This one was in a very poor condition, but we were poor, too; every cent we had went back into the business.”

Cue 250m3 of concrete poured to cover the first shed’s dirt floor and secondhand machinery purchased at auction; “I think we got more use out of it than the original owners did,” Warwick says.

Their five children were roped in to help on holidays and the plant expanded from one shed to two, eventually re-developing the entire near-1ha site.

“Most of our market today is in prefab frame and truss,” says Warwick, “but in those days we were often cutting for the furniture industry. It was a great industry to learn from, because it’s far more competitive than wall frames and roof trusses. It taught us a lot about utilisation: they’re supplying products to the retail market and at times the surface quality has to be 100% on all sides.”

From their experience working in other timber companies, the Drysdales knew that the same piece of timber that might fail as a 6m structural length could still be cut into pieces of, say, 2m of ideal structural product, 2m of surface grade product, and then 2m of lower-grade pieces suitable for pallets, etc.

By organising their business around the needs of multiple end users, their methods find a use for every one of those pieces: optimising the wood fibre recovery and reducing waste – and costs.

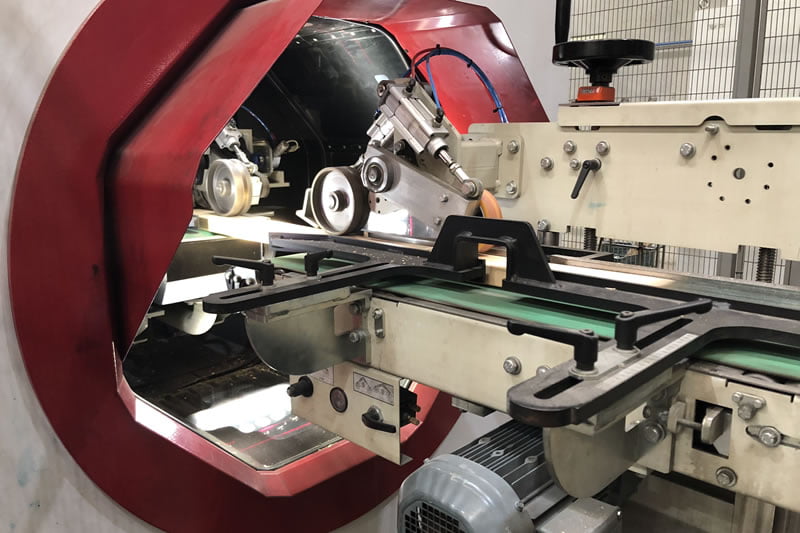

In the early days, assessments of each piece of timber were done by the company’s expert staff using traditional testing methods, but now a big X-ray scanner and some very sophisticated software does the job instead. Rows of boards are lifted from their pallets and fed through the machine, which runs at 80m/minute, going to a single saw cutting at 0.1mm tolerances (a second saw is on order to add a parallel line early next year). A real-time display on the computer beside the scanner shows the board’s qualities and makes decisions about what to cut out of it.

“We’re using extremely sophisticated optimisation algorithms,” says Warwick. “Especially when you consider they’re trying to optimise around a whole range of different defects: wood fibre grain angle, density, appearance… We’re running about 350 SKUs in our manufacture. We’re not trying to make them all at once on the one line, but we’re often chasing 18-20 out of one particular piece at any time.”

The level of detail in the resulting product is extremely high, and well considered. Timber destined for use in frame and truss avoids knots in cut ends, so nailplates will attach fully. Undersized junction blocks are produced to allow for a little imprecision when nailing them into place at the fabricating plant.

Bed slats for furniture makers are all solid board, but come in varying surface qualities – depending on the price point of the final product – with some versions bundled after cutting to go straight into the box at the customer’s end. “What matters most for slats is they have no sharp edges,” Warwick says. “So that’s one of the things we scan for.”

There’s a treatment plant on site specially designed for short lengths, where H2F Blue envelope treatments are applied to cut elements, minimising chemical and timber waste. Structural timbers are continuously monitored and externally verified and, where appropriate, information is printed onto the boards to help with compliance.

Programmed savings

While the timber cutting efficiencies are impressive, Programmed has built its success on the cost efficiencies it delivers.

“We’re a manufacturer’s manufacturer,” says Warwick. “We plan well ahead to ensure the right material is coming from the right producers, and align that with our customer’s needs.”

For frame and truss customers, Warwick points out that about 40% of the pieces in a truss roof repeat themselves from roof to roof. “We can produce those with an economy of scale, utilising recovered wood fibre. It’s a fully fit product, but it’s in short lengths. We cut angles on it, round ends… whatever’s needed. Then the fabricator can buy that bit from us rather than produce it themselves and concentrate on the elements unique to a specific roof.”

In addition to the savings from this mass customisation, products are supplied on an in-time basis, minimising storage needs at each end. Regular deliveries are set up for most customers with the production team. Business development manager Dee Atkinson uses the data to help customers plan. As Helen says, “We’ve done a lot of work in the software to bring up reports on the history of the customer. It empowers us to look at them and see what we need to do.”

Atkinson says it’s been an invaluable tool at both the Programmed end and for their customers. “We can use that information to help the manufacturers see their average use over the last 12 months and talk about how they plan to grow and how we can fit in production for them. It helps them to manage their inventory and it means we can plan from the feedstock through the production to the delivery.”

In the current housing downturn, the company has scaled back from their peak to 40 workers, but the turnover per full-time employee has improved. “In the boom, we were running above what our capacity should have been and throwing a lot of labour in to meet the demand,” says Warwick. ”The contraction has allowed us to really look at a lot of our processes and make them more efficient, and we’re taking that lesson out to our customers as well.”

A wider range of product now includes more precut componentry, freeing up more production time for customers and allowing them to scale up, or down, their orders in response to market movement.

Image: Timber is scanned to determine the best use of its qualities.