Use of engineered timbers externally comes with durability considerations. By Craig Kay, national product engineer, Tilling

Acknowledged as the oldest wooden building in the world, the Horyuji Temple in Japan was constructed around 700CE. In North America, covered timber bridges were popular in the 19th century, with the Hyde Hall Covered Bridge in Ostego County NY, built circa 1825, still functioning today.

Both the temple and the covered bridges are examples of design masterpieces that allowed untreated wood to survive, in the case of the temple, for over 1300 years. The basic design premise employed is to carefully detail the structure to limit exposure of the wood elements to water: an essential element for bio deterioration. Sacrificial timber elements in these structures keep the water away from structural components. For example, roof shingles can be replaced easily during routine maintenance.

Fast forward to the 21st century where the designer, builder and homeowner are presented with a bewildering array of building products to use both inside and on the outside of their house. Engineered Wood Products (EWP, also called engineered timbers) are taking over from most large section solid timber elements, some of which exhibited good natural durability. We need to carefully consider whether EWP are suitable to expose in modern structural applications.

The majority of EWP are manufactured from a Class 4 natural durability (AS 5604-2005) plantation wood fibre that, in its natural state, has a probable external above-ground life expectancy of 0–7 years. To improve durability, these products are preservative treated against insect and/or other biological hazards, making them fit for purpose for their intended end use. AS 1604.1 identifies these biological hazards by use of a hazard class number – Hazard Classes H1-H6 – to identify the degree of biological hazard.

External, above-ground applications subject to periodic moderate wetting and leaching (e.g. fascia, pergolas, window joinery, framing and decking) are classified as an H3 Hazard Class. Historically, the H3 preservative treatment processes were developed to give a piece of solid or round timber of Class 4 natural durability a probable external above-ground life expectancy of 15-40 years.

Within AS 1684.2:2010, Fig B1: Species Selection for Durability gives general guidance on the natural durability class or appropriate level of preservative treatment (hazard level) required to give an acceptable service life for various applications in the construction of timber-framed Class 1 and Class 10 buildings. This appendix is classified within this standard as ‘informative’ – while it is not an integral part of the standard, it is included for guidance, and depending upon the situation and some climatic conditions, the recommendations may need to be amended to suit.

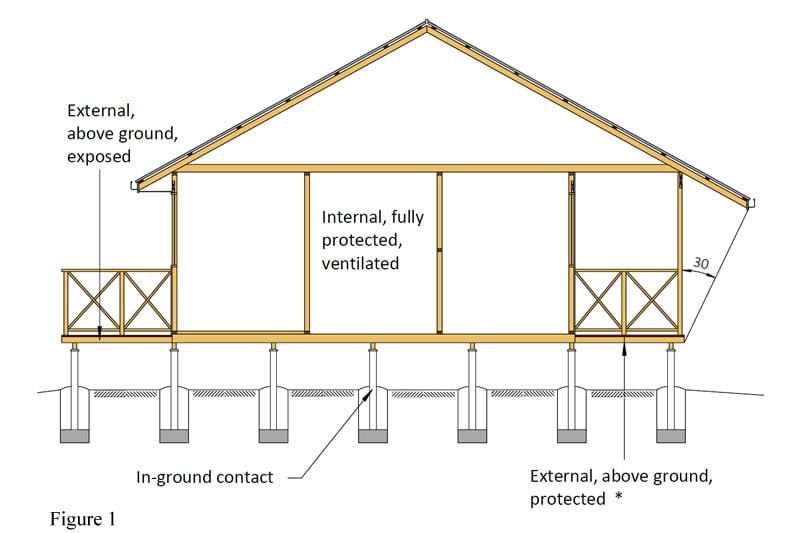

Figure 1 (top) shows four different areas within the building envelope. Table 1 (below) identifies the natural durability class or appropriate level of preservative treatment (Hazard Level) required to give adequate service life for each of these.

Table 1

| External, above-ground, exposed | • Above-ground durability class 1 timber with sapwood removed or sapwood preservative treated to H3 • Above-ground durability class 2, 3 or 4 timber preservative treated to H3 |

| Internal, fully protected and ventilated | • In- or above-ground durability class 1, 2, 3 or 4 timber |

| External, above-ground, protected | • In- or above-ground durability class 1, 2, 3 or 4 timber |

| In-ground contact | • In-ground durability class 1 timber with sapwood removed or sapwood preservative treated to H5 • In-ground durability class 3 or 4 timber preservative treated to H5 |

EWP are increasingly being used as bearers and joists for alfresco dining areas and covered decks, and also for post and beams for the roof structure.

Despite the above information being contained within AS 1684, and variants of it being reproduced in reputable EWP suppliers’ and Wood Solutions’ Design Guides, this advice is often ignored.

EWP bearers and joists that are external, above-ground, and exposed are required to be preservative treated to H3. But H3 is not a ‘silver bullet’; installation instructions from every reputable EWP supplier also mandate that the timbers must be correctly detailed to the following key factors:

- Shielding

- Drainage

- Ventilation

- Maintenance

Shielding

Shielding works by blocking or deflecting weather and moisture from direct contact with the EWP structure. It is especially important to prevent moisture being able to lay on horizontal surfaces of the EWP, such as deck joists, especially the cut edges.

Reputable EWP suppliers recommend the use of acrylic paint on all surfaces to protect the H3 timber from UV sunlight and general weather exposure. One major EWP manufacturer also includes in their Technical Data Sheets that parts of the EWP exposed to the sun be sheeted and top/end capped. See Figure 2 for a proposed solution for shielding the cut edge of an EWP decking component.

Drainage

EWP members and connections should always be designed to allow free drainage of water to prevent the development of moisture traps.

Ventilation

Ventilation prevents moisture accumulation from a variety of sources including rain, condensation and rising damp under subfloors. Building in air gaps between members allows better ventilation.

Maintenance

Maintenance of any weather-exposed elements is essential to the successful performance of EWP in weather-exposed applications. :

Create a regular maintenance scheme with inspections to focus on key areas such as:

- All horizontal surfaces

- Integrity of the paint system

- Joints, end grain and fasteners

- All capping elements

Prevent debris build-up between decking and joists. This debris can hold moisture and create a bridging for water between adjacent elements.

In short, this means excellent detailing and regular maintenance. It is that simple.

By following these principles, EWP, with their many length and span benefits for alfresco and patio applications, should provide the desired life expectancy – even if it may not be around 1300 years.

For more information on this topic, contact Craig Kay and the Tilling engineers via email at techsupport@tilling.com.au