Sweating the small stuff can make all the difference in trusses – and in boots. By Paul Davis

My ski boots fit me pretty well – except in one spot on the instep. I’m a week back from an eight-day trip and it turns out that that little misfit turns into an enormous discomfort in the long run. Days later my feet are still tender.

There are of course many little things that make a big difference; the trigger to the bomb, the seed that makes a plant, the “thank you” that makes a day. And, you guessed where I am going, there are many little things that make a trussed roof work; the span that fits the walls, the nailplate that carries the load, and the certification that gets through council.

In the modern world’s highly competitive environment, there is always a pressure to cut production costs. As my grandmother used to say, “Look after the cents and the dollars look after themselves.” So, quite reasonably, you may want to look at your nailplate sizes and attempt to lop a few dollars off each truss by reducing nailplate size. However, some plates are more critical than others, and it is worth getting a feel for the most critical ones where a reduction in size can more readily lead to trouble.

No doubt, your truss software lets you adjust the minimum plate size, probably in ways that may account for several different factors. There is, of course, a theoretical line that cannot be crossed, where the plate must be strong enough to resist the applied theoretical forces. However, if a plate is sized purely on these considerations, it may not take into account real world issues like plate misplacement, gaps between the timbers, incomplete pressing, timber variability, stresses set up during handling and imperfect truss plumbness in the roof. All of these factors can dramatically affect the strength – and so safety – of a nailplate.

So, if you are designing at minimum plate sizes, what are the most highly loaded and vulnerable truss plates? There is no universal answer, but in the majority of trusses, it will be the heel plate and apex plate.

These plates carry the highest loads in a truss. For example, a 20°-pitch truss has a force through the apex and heel plate equal to roughly three times the vertical load onto the top plate – that’s more than the weight of the whole roof on that truss!

Timber trusses sometimes amaze me with their ability to stay up in adverse circumstances (say, when butchered by a following trade). Nonetheless, when you are dealing with real forces equivalent to many hundreds of kilograms of weight, this can show up any weaknesses.

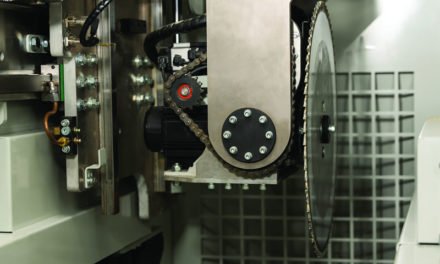

The failed apex plate in the image (above) is a classic example. The nails located near the very end of the web are largely ineffective because they can split out of the end of the timber. And, in fact they have done just that. So, there are only five teeth per side that are effective to carry load. The plate is vertically misplaced from its centre by two rows of teeth. If it had been correctly located centrally, then eleven teeth would have been effective and almost certainly the plate would not have failed. So, a reasonably small misplacement leads to a massive change in capacity and a dire outcome.

In the real world it is not possible to eliminate all fabrication inaccuracies. I’m guessing this was a 2.50pm on a Friday job. It was only due to luck and then some temporary props that this truss and the roof it supports didn’t catastrophically collapse over what is a nursing home lounge room.

This truss failed years after it was built. It is one of the quirks of timber that it is stronger in the short term than in the long. So, it may be that your business is occasionally putting out trusses with misplaced plates but you don’t know this is a major drama yet because these haven’t started failing yet. Nobody wants this, so, to limit the risk, I recommend not designing your plates right to the very limit.

Benjamin Franklin said: “Little strokes fell big oaks.” This is a case where little stuff-ups collapse big trusses. Put in a more positive way, being a truly good truss fabricator means being great at the little things!

Paul Davis is an independent structural engineer managing his own consulting firm Project X Solutions Pty Ltd. The views in this column are Paul’s and do not reflect the opinions of TimberTrader News. Phone: 02 4576 1555, Email: paul@projectxsolutions.com.au