Measures to guarantee safety have unintended consequences. By Craig Kay, national product engineer, Tilling.

The performance-based National Construction Code (NCC) regulates the suitability of building materials via Part A5, which details the approved “Evidence of Suitability” methods to demonstrate conformance with the code.

Industry had become concerned that some unscrupulous manufacturers were making fraudulent claims of conformance, and potentially putting lives at risk. The Lacrosse apartment building fire in Melbourne on 25 November 2014 galvanised support for action about the danger of non-conforming building products.

This renewed pressure resulted in the Senate, in June 2015, referring the matter of non-conforming building products to the Economics References Committee for inquiry and report by 12 October 2015. After lapsing because of the dissolution of Parliament for the 2016 election, it recommenced in October 2016.

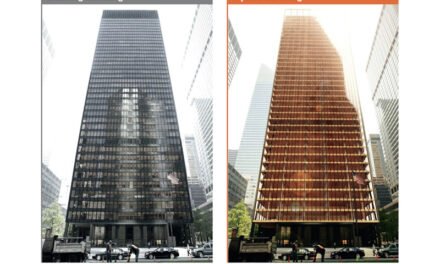

We’ll all remember the well-publicised fire disaster that happened in the 24-storey Grenfell Tower block of flats in North Kensington, West London in 2017. Though the fire broke out in a kitchen, it leaked out to the external cladding panels (containing polyethene cores) which acted as a source of fuel. The flames spread around the top of the building in both directions and down the sides until the advancing flame fronts converged on the west face near the south-west corner, enveloping the entire building in under three hours.

It was no surprise therefore, that the committee agreed to prepare an additional interim report on the implications of the use of non-compliant external cladding materials in Australia as a priority. The committee tabled its report, ‘Interim report: aluminium composite cladding’, on 6 September 2017.

CertMark International (CMI), a product certification body under the CodeMark Scheme, had also withdrawn nine certificates for cladding systems, including aluminium composite panels (ACP) and expanded polystyrene (EPS) in February 2019.

After the final committee report dated 4 December, 2018, the State Building Ministers commissioned a report entitled ‘Building Confidence’, written by Peter Shergold and Bronwyn Weir. The Australian Building Codes Board (ABCB) has recently issued a draft response to the Building Confidence report.

The senate committee introduced some new terminology that has now been reflected throughout subsequent documents, namely:

A non-conforming product or material is one that claims to be something it is not and does not meet the required Australian standard for the material—for example, the use of inferior grade material, or a product that contains illegal materials such as asbestos.

A non-compliant building product is one that has been used in a situation where its use does not comply with the requirements for such a material under the National Construction Code (NCC).

Building professionals will begin to hear these terms much more frequently and should understand how they differ.

INDUSTRY IMPACTS

So what has any of this to do with structural timber products typically found in domestic houses? While the catalyst has been disasters like these mentioned, the conformity of every building product will now come under much more scrutiny than any of us have been used to.

For many industry professionals, the mechanism that determines whether a building product such as a piece of MGP 10 framing can be used in a structure, is contained within the NCC, outlined in Figure 1 (see below).

For most timber products, there is a relevant Australian standard which is referenced in the NCC, which becomes the ‘deemed-to-satisfy solution’, e.g., MGP framing – AS/NZS 1748.1, AS 1748.2 and AS/NZS 4490.

By stamping AS/NZS 1748 on the timber, producers of MGP framing are not simply branding their product, they are making a legal statement that their product conforms in all respects to that standard. Consequently, conformance to that NCC referenced standard satisfies the Performance Requirement by being a Deemed-to-satisfy Solution.

Whilst deemed-to-satisfy provisions have not changed, the heightened sensitivity about conformance is already seeing specifiers and regulators requesting evidence of the verification of the stated properties. Regulators may now begin asking for previously unheard-of amounts of product verification.

Currently some structural timbers used in domestic housing that may not be manufactured under a specific Australian Standard referenced in the NCC do, however, conform to the NCC as a ‘Performance Solution’ and typically utilise one of the Evidence of Suitability options listed in Part A5.2 of the NCC, commonly A5.2(1)(e) – a certificate or report from a professional engineer.

Amendment 1 of NCC 2019 released on 1 July 2020, introduced in Part A2.2 a new Item 4, which now defines a four-step process where a Performance Requirement is proposed to be satisfied by a Performance Solution. There was, thankfully, a 12-month delay in the implementation of this amendment, meaning that come 1 July this year, the landscape for some common timber-based products will dramatically change.

So involved and complex is this new requirement, that the ABCB released a four-page document entitled ‘Performance Solution Process’ in July 2020, available at www.abcb.gov.au.

This is where the term ‘collateral damage’ in this article’s title comes in. The precepts and requirements do make sense where a new project like the Lacrosse Tower is being proposed. In that instance it is acceptable and practicable that stakeholders consult at the concept planning stage, and ultimately agree to the Performance Solution methodology.

It is however totally impractical for this process to be adopted for every domestic dwelling where the design includes timber-based product with no dedicated Australian Standard, but manufactured to conform to the NCC via and Engineers Certification. These common materials may include OSB (e.g., wall bracing panels, I-joists), open-webbed floor trusses and basic items like joist hangers. The list could go on and on.

These totally reliable and long-standing solutions that have been so important to the industry have become collateral damage in efforts to prevent another Grenfell Tower-type disaster.

The ABCB published a handbook titled Evidence of Suitability in Jan 2018 as a companion document to the evidence of suitability provisions in A5.1, A5.2 and A5.3 in each volume of the NCC. An updated and amended version of this document was published again in September 2020.

Thankfully, the NCC has added an extra evidence of suitability for product in Part A5.2. item (f) introduces “Another form of documentary evidence, such as but not limited to a Product Technical Statement”.

A Product Technical Statement (PTS) is a document stating that the properties and performance of a building product fulfil specific requirements of the NCC. In essence, it provides a checklist of every performance requirement in Part BP1.1–1.2 and provides evidence that these requirements have been satisfied with this product within the defined limitations of use.

Although regulatory authorities have started requesting these documents as of 1 July, 2020, these provisions do not take effect until July this year. Come this time, it is likely the demand for PTS’s will increase significantly, so it is vital that all stakeholders in the timber supply chain understand not only what these documents are, but have access to them if required.

The silver lining for responsible timber producers, if there is one, is that this requirement will clearly delineate the competent and legitimate structural timber suppliers who can fully demonstrate Product Conformance, and those who sell product of dubious provenance without evidence of strength and quality.

Heraclitus, the Greek philosopher said, “Change is the only constant in life.” How correct he was.

For more information on this topic, contact Craig Kay and the Tilling engineers via email at techsupport@tilling.com.au